The Man Who Came to Dinner is a Madcap Comedy That Builds a Whirlwind of Surprises (3 stars)

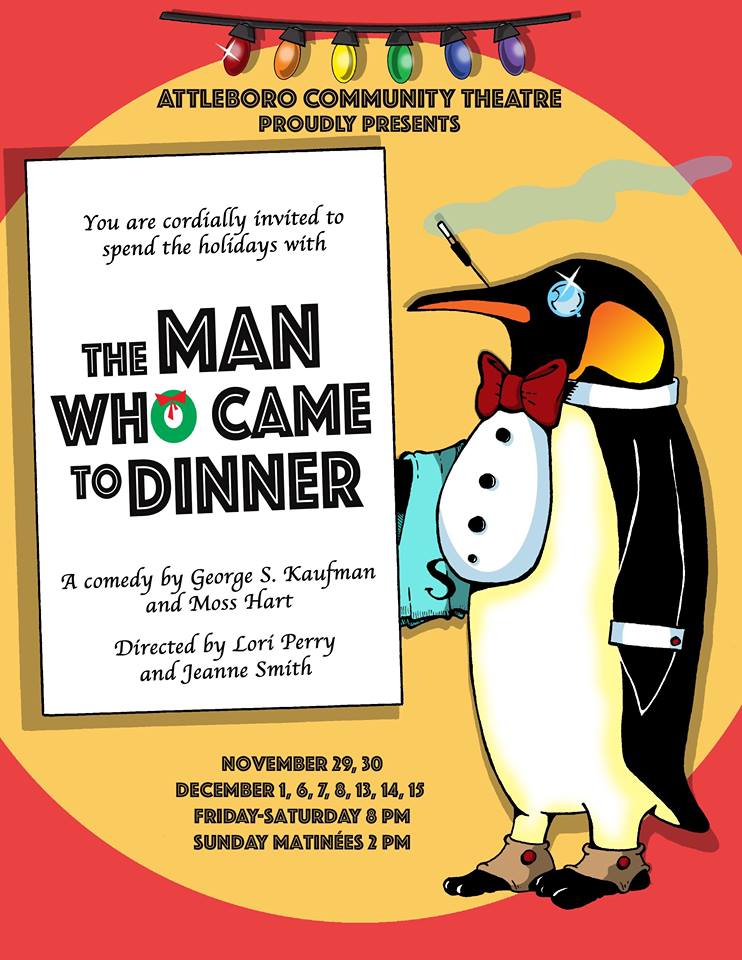

The Man Who Came to Dinner, directed by Lori Perry and Jeanne Smith, stage manager Kimmi Roche, lighting design by Johnny Kelly and Scott England, sound design by Shawn Perry, costumes by Jeanne Smith, Alex Aponte, and cast, and set design and dressing by Jeanne Smith, Lori Perry, and Kimmi Roche, ran November 19 to December 15, 2019 at the Attleboro Community Theatre in Attleboro, Massachusetts.

In The Man Who Came to Dinner, Sherry, a cantankerous radio personality, comes to dinner at a private home, slips on the ice, and hurts his back. When he threatens to sue, they house him and attend to his every need while he’s confined to a wheelchair, despite his caustic remarks and increasingly unreasonable demands! It all takes place at Christmastime, and being a comedy, you can guess that the end will be happy. (It reminds me of an episode of the TV show The Partridge Family or I Love Lucy.)

The show is hosted in the basement of the Ezekiel Bates Masonic Lodge, which seats 150. They serve homemade snacks including cupcakes, brownies, popcorn, and drinks, and hold a raffle. Seats are comfortable. The play is not to be confused with Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner, the race-relations film.

I’ve heard that Boston is a tough town for comedy, because we’re stoics and because we’re smart enough to see a punchline coming. It’s even more of a challenge in a small theatre, because it takes a critical mass of audience members to get waves of laughter going. Still, the Attleboro Community Theatre proved they could do it with I Hate Hamlet (4.5 stars), a comedy that went far above local theatre expectations.

Having nothing to do with the Attleboro Community Theatre or its directors, as it was written in 1939 the script for The Man Who Came to Dinner is problematic in four fundamentals.

First, at more than 2.5 hours (including two intermissions), the play is too long, with some passages that don’t move the story along. Beverly tells a long story about an unrelated event that took place elsewhere off stage. There’s a long phone call about a wedding that’s not only unrelated to the plot, but also we can’t see the other party on the phone.

Second, the play is one of those madcap comedies where more and more plot threads emerge, growing into a whirlwind of chaos… but some of its threads drop out instead of being maintained to the end.

Third, we’re not sure who the straight man is. In his autobiography, Chuck Jones, the creator of Bugs Bunny, says that when the protagonist is a strange character who surprises ordinary people, that’s farce, and farce isn’t funny. Think of the movie, Pee-wee’s Big Adventure (1985). Bugs Bunny cartoons are comedy because the protagonist, Bugs Bunny, is an average Joe, but tormented by strange characters: the Martian, Elmer Fudd, and the Tasmanian Devil.

In The Man Who Came to Dinner, sometimes Sherry is the straight man beset by troubles; sometimes he’s causing the troubles. It’s confusing. The play begins with a central conflict between Sherry and Mr. Stanley, but shifts to a conflict between Sherry and his assistant, Maggie Cutler.

Finally, the narrative line is not clear. Sherry makes a major transition in the play, but this is telegraphed too early. Why is he at times nasty and at times warm-hearted? Two romance stories seem to come out of nowhere. When Sherry does eventually make his transition, the emotional change of heart is not well supported in the script. (In A Christmas Carol, Scrooge has his major change of heart when the Ghost of Christmas Yet To Come stunningly shows him his own grave!)

These issues with the script are no fault of the Attleboro Community Theatre, of course, except perhaps that they chose a script that contained some story flaws, and also that the script contained too many production challenges.

One way in which the play was too hard to produce is that the main character, Sherry, is nasty but supposed to be likable, too. Think for example of Nathan Lane in The Producers, who plays a criminal, but because his performance is cartoony, there’s no real pain there when he defrauds others. That is a tricky balance for an actor, and to make it even harder, in The Man Who Came to Dinner, the actor who plays Sherry is also confined to a wheelchair for the play, limiting his range of motion. I am sorry to relate that Bruce Church (Sheridan Whiteside) was not quite up to this challenge. He portrays a radio show host, but didn’t dominate the room with his personality. His quips had too much bitterness to be likable.

Another reason the play is hard to produce is that it’s is a parade of strange characters and subplots, and thus each character gets very little time on stage. That’s a challenge for a cast to get the audience to connect emotionally and to always follow what is happening. Think for example of the film Twelve Angry Men, about a jury of twelve people. It’s so many that they’re given strikingly different costuming and personalities so that we can tell them apart, and each nuance of dialogue counts because we only get so much time with each. It’s a big hurdle for a theatre troupe to present such a play powerfully and clearly. (The trick is to lean into stereotypes to quickly establish each personality.)

Thankfully, in the Attleboro Community Theatre production, many of the supporting cast did exaggerate their characters and use stereotypes to good effect. At its best moments, The Man Who Came to Dinner was hilarious. Kudos to Mike Capalbo (Professor Metz / Banjo), Tom Lavalle (Beverly Carlton), and especially Ryan Foster (Lorraine Sheldon) with her nutso parody of a rich and shallow actress.

These actors and others made the show. They used physical humor to get laughs that weren’t even written in the script. Doctor Bradley (Jeffrey Massery) and Jim Poore (Bert Jefferson) had their moments of physical antics, too, the Doctor at one point being invited to a meeting, saying “Okay! I’ve got just one patient who’s dying, and then I’ll be free tonight!” The best actor in the cast was Joyce Leven (Maggie Cutler, the assistant), who showed a wide range, convincingly being sometimes mean, sometimes hurt, sometimes in love, sometimes earnest, and sometimes playfully nuts. Great job.

There are tradeoffs to community theatre. On the plus side, you get to root for the home team, as you do in improv comedy. And in community theatre, where everyone has a day job, they can only get through it with exceptional passion — a passion that often shows in a production. On the negative side, you expect some level of amateurism. In this production of a Man Who Came to Dinner, the cast did not use microphones and some of them did not project to the back with diction and volume.

These are easy things to correct, so I suspect they may have just run out of rehearsal time. Nobody flubbed a line that I noticed. A few times, actors rushed their lines, or didn’t connect their dialogue to the other actors, reacting to each other.

Speaking of reactions, that is another secret to comedy. I once read that in the old-time vaudeville days, the straight man would actually get paid more than the comedian, because the audience doesn’t laugh at the comedian until the straight man reacts awkwardly. We did see some marvelous awkward reactions in The Man Who Came to Dinner. For example, at one point Sherry gets so mad that, in frustration, he beats his fists on his own lap like a child! The best laugh of the night was when Lavalle reacted by putting a hand to his chest in shock and just said, “No!” At another point, someone is surprised and drops a lit cigarette into his own lap.

Unfortunately, too many times I would loved to have seen more reactions and physical humor. For example, the feud between Sherry and Mr. Stanley did not heat up to the level of steam coming out their ears with indignation, through their body language and tone of voice. (This is mitigated in part because, as I mentioned, the play veers in another direction midway through, to being a tale mainly about Sherry and his assistant.)

Staging, by Jeanne Smith, Lori Perry, and Kimmi Roche, was the interior of a private home, decorated with Xmas dressings, tree, wallpaper, brown tones, and even an old telephone. Props to the propmaster for getting that old phone, and an old-timey wheelchair, too! (I was also impressed with Jessa Leavitt as propmaster for I Hate Hamlet, too.) Unfortunately, the interior suggested more of a middle-class home, not a wealthy home with servants. When the doorbell rang, the audience naturally looked for the door, but the staging placed the home’s entranceway out of sight.

The play has two intermissions, with big band swing music. The song “What Am I To Do” was written by Cole Porter specifically for The Man Who Came to Dinner in 1939, but if they sung it, I have no memory of a song in the show and it’s not in my notes. Costuming did not play its role in supporting the emotional arc of the characters. The character Banjo was modeled on one of the Marx Brothers, but wasn’t costumed or performed that way.

At the end of The Man Who Came to Dinner, there is finally an escalation, a whirlwind as the remaining plot points all come together to antagonize… whomever is supposed to be the straight man, Sherry I guess, even though he’s also the main instigator. Then there are a couple of satisfying plot twists and all ends well in a good final last scene, although with a couple of strange moral choices involving an Egyptian sarcophagus and an unsolved murder.

Having seen the heights that the Attleboro Community Theatre rose to with I Hate Hamlet (4.5 stars), I suspect that this script was just too challenging in its needs and tangled narrative structure. In future productions, I am sure they will rise to heights again. This time, only 3 stars for The Man Who Came to Dinner.

In February, the Attleboro Community Theatre produces Over The River and Through the Woods, another comedy. When a carefree bachelor in New Jersey gets a job offer to leave town, his shocked, very Italian and affectionate grandparents conspire so he won’t leave them.

See Attleboro Community Theatre online.