See the Declaration of Independence at the American Independence Museum (4 stars)

The American Independence Museum is a series of exhibits in a historic home, the Ladd-Gilman House, built in 1721, and which became the New Hampshire governor’s mansion. It’s based in Exeter, New Hampshire, which was founded in 1638, became a busy seaport in early 1700s, and was New Hampshire’s capital during the American Revolution. Don’t park at the bank. There’s two-hour street parking on Center Street and a municipal lot nearby. Ask for the guided tour. The museum runs May through November.

The museum tells the history of Exeter and especially the Gilman family, who lived in the house. Nicholas Gilman Jr. was delegate to the Continental Congress in Philadelphia, and a signer of the US Constitution, representing New Hampshire, and later served in congress. His brother, John Taylor Gilman, became Governor of New Hampshire for 14 years, with the building serving as a government house for a time. He also funded Phillips Exeter Academy.

The museum tells the history of Exeter and especially the Gilman family, who lived in the house. Nicholas Gilman Jr. was delegate to the Continental Congress in Philadelphia, and a signer of the US Constitution, representing New Hampshire, and later served in congress. His brother, John Taylor Gilman, became Governor of New Hampshire for 14 years, with the building serving as a government house for a time. He also funded Phillips Exeter Academy.

The Ladd-Gilman House has its original walls and floors, so with the exception of being wired for electricity, it’s quite authentic, with its floor painted a ruddy clay red and its window shutters painted light olive green. One exhibit shows how the original building was expanded over time. Intriguingly, the floors are sometimes uneven or sloped, and some of the window panes are original glass, not perfectly flat like you would see today. Watch your head passing through each doorway!

Forget the Battle of Lexington and the “Shot Heard ‘Round the World”. Here in Exeter they claim that the American Revolution really began four months earlier in nearly Portsmouth, New Hampshire, when 400 local citizens surrounded Fort William and Mary and took the British gunpowder. Behind the American Heritage Museum you can see the old storage house where the stolen gunpowder was kept.

You’ll also find a colonial kitchen with a ‘toaster’, a metal encasement with a spit and holder for toast. There’s a chest where they used to keep the tax money, an old-time military chest, muskets on display, and an exhibit on weaving flax. An archaeological dig on site has uncovered a Native American arrowhead and a few other items. There’s a fireplace in every room, and old-time, dark wood furniture including old woven cane chairs, and a 19th century copy of George Washington’s Mount Vernon writing desk.

But the majority of the exhibits at the American Independence Museum are flat. There’s a print using a Paul Revere etching of The Boston Massacre, and a “trial book”, printed on an old-time printing press, a transcript of the Boston Massacre trial. There’s a printed copy of New Hampshire’s original constitution.

Hanging on one wall is a “proclamation” from New Hampshire for its citizens to hold a day of fasting and prayer, to more devoutly serve God, so that the Revolutionary War would go better. You’ll also see a 13-star flag from the 1876 centennial celebration.

There’s a printed draft of the Constitution with handwritten notes from 1787, and one of two still existing original purple hearts from the Revolutionary War, issued by George Washington. It’s just cut from cloth. (Modern purple hearts weren’t issued until President Herbert Hoover in 1932.)

Out back you’ll also see Folsom Tavern, which is not open to the public except for special events. George Washington once visited the tavern and it became the local meeting space of the Society of the Cincinnati, a veteran’s organization.

One room of the American Independence Museum is given to the Society of the Cincinnati. There’s a copy of the Gilbert Stuart portrait of George Washington where the artist added a medal of the Society of the Cincinnati. They display china dishware and a big case of medals that all come from just one general! And a display for other members who served in World War I.

There’s an embroidery on one wall, and an old map showing all the original towns of New Hampshire. Another display highlights the women’s suffrage movement, and local voting in New England.

Of course there’s a small gift shop with handmade soap, dishes, mugs, t-shirts, books, and tea.

My guide displayed great energy and an encyclopedic knowledge of history. Her enthusiasm was infectious, though sometimes we’d get lost in the details. We’d enter a room and she seemed so eager to discuss a particular item that we skipped over the context which, as a brand-new visitor, I needed. (Here I’m thinking of the Longfellow House in Cambridge, whose guides tell a well-connected story as you walk through the former headquarters of George Washington.)

Its exhibits are adequately curated, but mainly wall text, without dioramas, mannequins, special content for children, or interactive displays. (Here I’m thinking of the Harriett Beecher Stowe Center, which doesn’t contain much but somehow is full of pizzazz.)

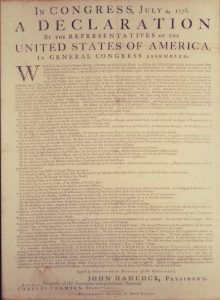

So there isn’t that much to see visually, compared to the numerous other historic home museums in New England. But it does have a stunning first printing of the original Declaration of Independence, which was delivered to New Hampshire on July 16, 1776, which is why Exeter celebrates its Independence Day on whichever Saturday is closest to July 16. And they hold special events which sometimes have costumed visitors from the past, such as the Ghosts of Folsom Tavern and Winter Street Cemetery Tour coming soon for Halloween, beer events at the Folsom Tavern with scavenger hunts and colonial games, Revolutionary Story Time, for small children.

I’ll give the American Independence Museum 4 stars.

For more, see the American Independence Museum online.