Six-Time World Champ Emile Griffith Holds No Punches in Search of Redemption in “Man in the Ring” (5 stars)

“Sometimes you got the sun in your pocket and you still go out looking for the dark.” This among the plethora of earnest and didactic one liners in the Huntington Theatre production of “Man in the Ring” written by Pulitzer Prize winner Michael Cristopher and directed by Michael Greif; showing at the Calderwood Pavilion at the Boston Center of the Arts Nov. 16 through Dec. 22.

“Man in the Ring” attempts, and to a large extent succeeds, at gifting the audience with a heart-shaped emotional odyssey, a little more than a dram from the life of six-time world champion pugilist (fancy name for boxer) Emile Griffith, marred with abysmal tragedies and towering triumphs in his ever ending search for forgiveness and redemption from the darkest parts of his salacious life. The play offers an eagle-eyed glimpse into the boxing great’s life stemming from meager origins in the U.S. Virgin Islands of St. Thomas and through his indiscretions, scandals and turmoil—whether having to do with his love life, familial woes or professional setbacks—that came to define his moments of reckoning with his sexual orientation (which could possibly explain why most have not heard of him until now) and his fragmentary search for identity, acceptance and deliverance.

“Emile Griffith is a black Caribbean American…who came to New York as an immigrant hoping to be a baseball player or singer,” said playwright Michael Cristofer—whose screenplay credits include “Falling in Love” with Meryl Streep and Robert DeNiro and “The Witches of Eastwick” with Cher and Jack Nicholson—when asked by Director of New Works Charles Haugland about what ignited his interest in Griffith’s story. “He was drawn into becoming a boxer—which he didn’t have a passion for to begin with—but then found the passion and had a very long career.” But more importantly, Cristofer emphasized that his ability to connect to Griffith’s story on a personal level was what really singed his desire to write the play, “I’ve been offered jobs to write about a certain subject or a certain character, and I’ve felt no connection. Then [I] can’t do it. But when that mysterious thing happens and you feel that their voice and your voice have a similar connection, then it can be done.”

Cristofer expounds on this “connection” when he went on to say, “I grew up in an Italian ghetto where the definitions of masculinity were strict and I [too] had struggled with my sexuality… [Like Griffith] there was a sense of wanting to make peace with my past. I saw in his story, a man slipping into dementia and trying to make peace…He was a young immigrant…struggling with his identity while in a brutal sport… [Trying] to find peace amid the love, pain and joy that was his life.”

The issues of Griffith sexuality was omnipresent throughout the play, yet it did not obliterate other aspects of his life, for example his complex and at times accusatorial relationship with his mother, his questionable “marriage” and his palpable, sympathetic and searing relationship with his lifelong partner all assembled to make for an extravagantly inventive and studied production.

Described by some pundits as impressionistic, this visually vivid and lavish conception of “Man in the Ring” offers the audience a cornucopia of philosophical, spiritual and mostly convivial and jovial spectacle involving authentic Caribbean song and dance, sunny period costumes and lush set designs and props by David Zinn—Tony Award Winner for SpongeBob SquarePants—that weaved in and out seamlessly on stage right before our very eyes; rendering the impression of a close-up magic act.

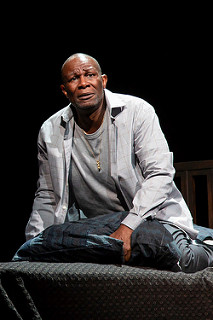

Tony Award nominee John Douglas Thompson, whom I jawed with after the show, gave a heartfelt emotional rendering as the older Griffith in tandem with his St. Thomas accent, which he effectively delivered with lapidary clarity. The accent, according to Thompson, took about a month of training to master since Thompson himself was born in England to Jamaican parents and lives in Brooklyn, New York. Some of his film credits include “The Bourne Supremacy”, “Michael Clayton” and “Wolves”. His portrayal of the reflective and mentally deteriorating Griffith was at times farcical but nonetheless touching, realistic and haunting, evoking compassion in lieu of pity, understanding and benevolence in lieu of judgement and indifference.

Kyle Vincent Terry gave an ebullient, boisterous, nuanced and thoughtful performance of the younger Griffith. A Brown University graduate with a Masters of Fine Arts and whose television credits include—“Elementary”, “Bull”, “Madam Secretary” among others—commanded the attention of the audience in hypervigilant fashion, replete with youthful adrenaline, esthetical ease, gregarious grace and perhaps inadvertently or even deliberately radiating palpable sexual energy with his pelvic thrusts and well-defined muscular body. The chemistry between the cast was most definitely and unequivocally electric and readily apparent.

This production was able to pluck the heart strings of compassion from some of the most seemingly stoic audience members. One man began to shift uncomfortably in his seat and was soon wiping streams of tears during a particularly poignant moment towards the end of the play. Hip-Hop artist and music mogul Sean “Diddy” Combs once said “great art” should make you feel “uncomfortable” especially when you are sharing the experience with other people around and I can definitely attest to feeling “uncomfortable” many times over at the shear emotional rawness that was depicted before me.

The erotic scenes, as uncomfortable as they were at times for me personally, were tastefully and artfully done, as young Griffith explored the physical components of his sexuality, which was purported to be indubitably ambiguous. He pranced around the stage in a devoted regimen of partial nudity. His heavily muscled body glistened, thundered, stomped and commanded our attention like a swashbuckling giant. His physicality simultaneously menacing and alluring in his resilient and youthful attempts to find himself as a black sexually ambiguous professional boxer during the 1950s and 60s, when masculinity was very narrowly defined; on his way to reaching the zenith of boxing stardom.

“Sometimes you have to reach for what you can’t reach, sometimes you have to reach for what you can’t even see,” the older wiser Griffith character earnestly utters which denotes the plays message of faith, hope and optimism, which I found particularly relatable to our current turbulent epoch here in America and elsewhere as the need for macrocosmic hopes for peace becomes more and more pressing. Even 18th century German philosopher Johann Wolfgang Von Goethe centuries before demonstrates concurrence when he affirmed that, “In all things, it is better to hope than to despair.”

The theatre was invented as a beacon of hope for the human race; it was designed to help connect us to each other, to mitigate our collective sorrows, celebrate our collective joys and harmonize our human hearts. 18th century English poet Alexander Pope agrees with this ideology when he wrote that the theatre’s purpose is to “wake the soul by tender strokes of art, to wake the genius and to mend the heart.”

“Man in the Ring” is an affecting primrose heart mending production, imbued with perennial true to life tufts of motley characters, rousing and sensual dance numbers, exceptional and fantastical acting and directing. See it this holiday season; it may just help you find your own form of redemption. 5 stars.

Jacques Fleury’s books Sparks in the Dark: A Lighter Shade of Blue, A Poetic Memoir about life in Haiti & America was featured in the Boston Globe. It’s Always Sunrise Somewhere and Other Stories is a collection of short fictional stories spanning the pervasive human condition. Their topics range from politics to romantics, from sex to sexuality, from religion to oppression. His CD “A Lighter Shade of Blue” as a lyrics writer with neo-folk group Sweet Wednesday” is available on ITunes. For more information, visit: www.authorjacques.com.